What does a £2,500 record sound like?

Audiophile Pete Hutchison has gone to extraordinary lengths to reissue golden era classical recordings in their purest form. He talks to Killian Fox about the price of perfection, the ‘digital con’, and the sound of a truly analogue recording.

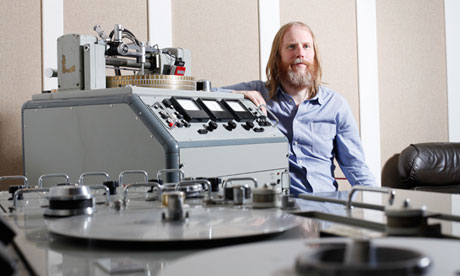

‘It’s not just about vinyl, it’s about a whole philosophy’: Pete Hutchison in his studio in west London. Photograph: Katherine Rose for the Observer Four years ago, Pete Hutchison realised that his record-collecting habit was getting out of control. From a young age he had been buying music across a wide variety of genres – folk, rock, punk, jazz, house and techno – but recently he’d been getting into classical music, and that, for a lover of rare vinyl, is an expensive move. Classical music tends to fetch much higher prices on the collector’s market than other genres. “In a single year,” he says, “I spent £40,000 just on classical, not counting all the other music I was buying.” One purchase that year, a rare box set of Mozart recordings from 1956, set him back £7,000. Seeking to address the problem, Hutchison decided to take matters into his own hands. Since 1991 he has been running Peacefrog, an indie label that has enjoyed considerable success in recent years with acts such as José González and Little Dragon. His label’s distributor was EMI, which held the rights to a formidable collection of classical recordings. Through his contacts there, Hutchison got permission to remake 80 celebrated recordings from the so-called “golden era” 1950s and 60s and reissue them himself, via his new label the Electric Recording Company. The first limited-edition repressings, three sought-after LPs of Bach sonatas played by the Hungarian violinist Johanna Martzy. They went on sale last November, priced at £300 apiece. The second reissue was the rare Mozart box set. A collection of the composer’s complete Parisian work on seven discs, directed by Fernand Oubradous, and limited to 300 copies, it will cost you £2,495. These are no ordinary reissues. Hutchison’s purism as a collector, it turned out, was outstripped by his perfectionism in the studio. Many vinyl reissues are produced cheaply and quickly on contemporary machinery. Hutchison insisted on doing everything as it would have been done half a century ago, but with added perfection. “I want to have the best-sounding records in the world,” he says. Naturally, this wasn’t going to come cheap. “The first challenge,” he tells me when I visit him at his studio in Notting Hill, London, “was finding and restoring the equipment.” A willowy man with long hair and a gratifyingly bushy beard, Hutchison is every inch the obsessive audiophile, and now he has the machinery to match. The EMI reel-to-reel tape recorder on one side of the room, which had to be fully restored, would have been used at Abbey Road to record the Beatles and the Stones. The mastering console in the centre, also built by EMI, came from Nigeria – but the real find, Hutchison tells me, was the pair of contraptions to our right: a valve-powered tape machine the size of an Aga and a vinyl-cutting lathe, both manufactured by the Danish company Lyrec in 1965. Hutchison found the two machines “shipwrecked” in a council garage in Cheshunt, bought them for £10,000 and spent three years and “10 times” the purchase price rebuilding them with the help of veteran sound engineers Sean Davies and Duncan Crimmins, guided by instruction manuals Davies had kept since the 1970s. Valve technology all but disappeared in the mid-70s, when the studios switched over to cheaper transistors – a travesty, in Hutchison’s view, exceeded only by the subsequent switchover from analogue to digital. “The problem with transistors is they sounded a bit hard and glassy,” he explains. “They didn’t have the texture and open top-end of the valve sound.” Now he is bringing that lost texture back to life. “These, we believe, are the only machines in the world capable of producing an all-valve stereo cut.” When they put out their first stereo release in July (the Bach and Mozart records are mono), it will, he claims, be the first all-valve stereo cut in almost half a century. Having paid so much attention to how his product would sound, Hutchison didn’t want to skimp on appearance. “The sleeve and artwork design and manufacture had to be done as it was in the 50s,” he decided. In east London, he tracked down an artisan printer with a 1959 Heidelberg letterpress and set him to work. Everything had to be authentic, right down to the vintage gold paint and the silk cords, and nothing could be scanned: even the images had to come from the original photographs, which meant tracking down the photographers, or their children, to request permission. The 50-page booklet accompanying the Mozart box set took an entire year to make . When Hutchison plonks the £2,495 item in my lap, informing me that it’s probably the most expensive record ever made in terms of manufacturing costs, I open it nervously and peek inside. It’s a beautiful object, and the attention to detail is astonishing. But has all this effort really been worthwhile? Financially, perhaps not. Although he says he’s recouped 50% of the manufacturing costs for the first two releases since November (they are still coming out on a drip-feed basis), breaking even on the entire project will take a lot longer. “Possibly my kids might recoup it,” he says, laughing. Money, it seems, isn’t the main issue here. Hutchison tells me with obvious pride that when a writer for the American magazine Stereophile got his hands on the Mozart box set, “he said it was the most expensive record he owned but by far the best. And that was a great accolade: success to me is more about getting the respect of individuals like that than it is about the financial side.” Reading this on mobile? Click here to view video It’s also about drawing attention to superior technologies that have been neglected in the scramble to do things in cheaper and more convenient ways. It would be easy to read the project as a critique of the digital era, and in fact Hutchison represents it quite openly as such. “It’s not really just about vinyl,” he says at one point. “It’s about a whole philosophy: it’s the aesthetic, it’s the sound, it’s everything.” In terms of the listening experience, digital, he says, “is the great con. They said that CDs were indestructible, but they weren’t. They said it would sound better, but with the MP3 we are at probably the lowest point in the history of sound. It’s a compressed file. If you try to play an orchestra over a proper sound system on MP3, it’s just garbage.” Hutchison has bigger criticisms to make about digital culture – we have become slaves to our technology; the distractions of mobile phones and social networks are threatening creativity – but, I wonder, is this project really the best way to get those points across? How effectively can a philosophy be expounded if it costs hundreds, even thousands of pounds to buy into it? Hutchison acknowledges that exclusivity is an issue. “We’ve had some comments where people have said, ‘I wish I could afford these records, why does it have to be so elitist?’ The reason is simply how much these things cost to make – it’s a bit like Aston Martin making cars at a loss in the 60s. But I think now that the technology’s settled, we can look to do some stuff that’s a bit more affordable to some people.” In July, the Electric Recording Company will put out its third release, a 1959 stero recording of Leonid Kogan playing Beethoven’s violin concerto, conducted by Constantin Silvestri. Further ahead, Hutchison has plans to move beyond classical music into rock, jazz, and other genres with a broader appeal, which would help lower the price somewhat. “They would sell more so we could press more and maybe do them around the £100 mark,” he says. Still not fully convinced, I ask Hutchison if his products are for audiophiles only; or would the average listener be able to make out the difference in sound quality? “Anyone could tell,” he says. To prove his point, he places one of the Bach LPs on to a turntable and lowers the needle. Across a gap of more than half a century, Johanna Martzy’s violin begins to play. It’s not only the music that’s extraordinary: the sound is warm, textured, gorgeously nuanced. We sit in silence for a few moments, marvelling at the clarity. Save for a few little crackles here and there, it’s perfect. Original article by Killian Fox, The Observer, 25 May 2013 reprint under NLA licence AL 00055357